HL Nucleophilic Substitution

Recap:

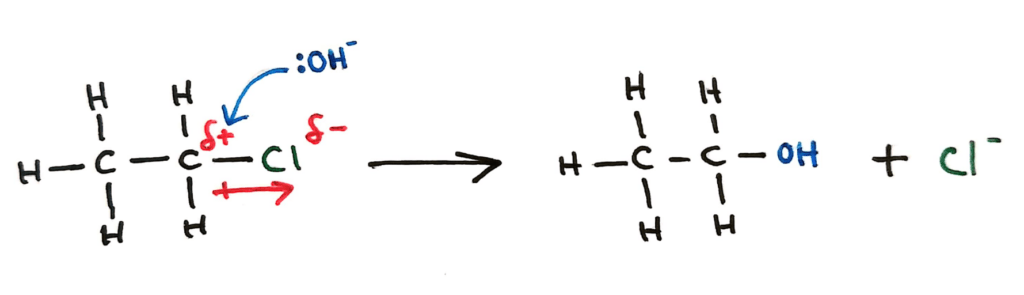

Nucleophilic substitution is a sort of displacement reaction in which a nucleophile will react and substitute out (usually) a halogen group.

^^This is what it looked like in Topic 10 (SL). In topic 20 it gets way cooler….^^

SN1

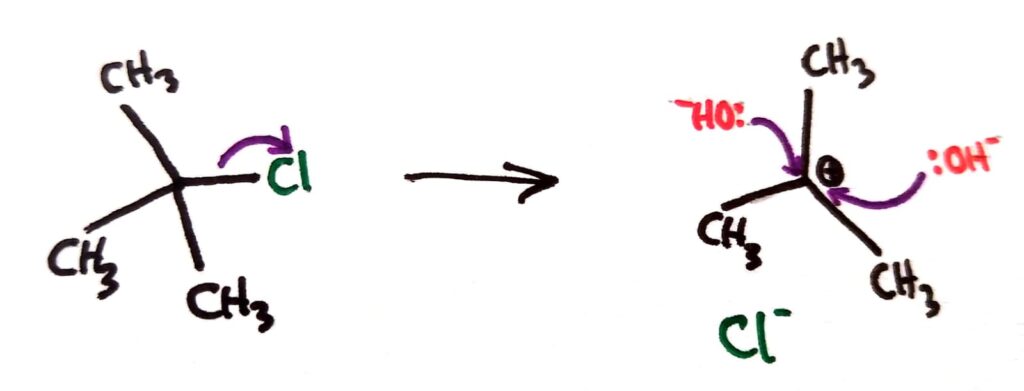

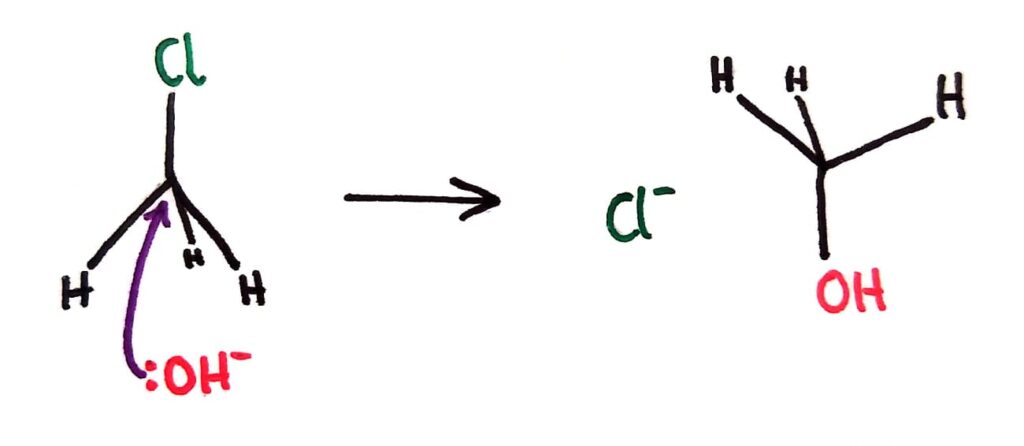

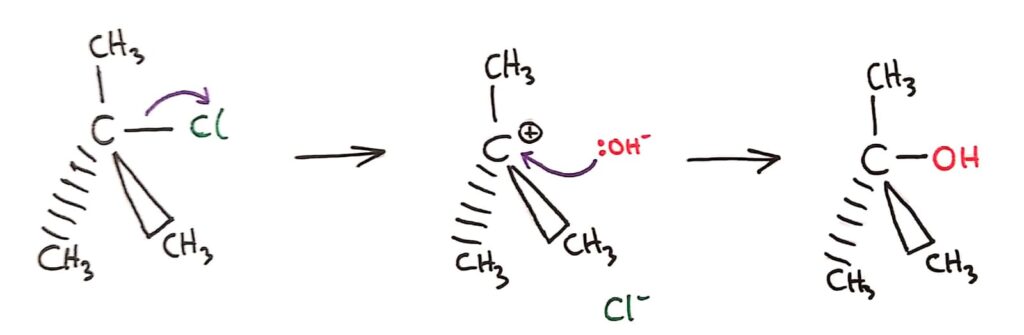

SN1 represents a nucleophilic unimolecular substitution reaction and SN2 represents a nucleophilic bimolecular substitution reaction. SN1 involves a carbocation intermediate. SN2 involves a concerted reaction with a transition state.

Deduction of the mechanism of the nucleophilic substitution reactions of halogenoalkanes with aqueous sodium hydroxide in terms of SN1 and SN2 mechanisms.

In SN1 reactions, the C-Halogen bond breaks forming a carbocation intermediate. The positive carbocation then reacts with the nucleophile.

SN2

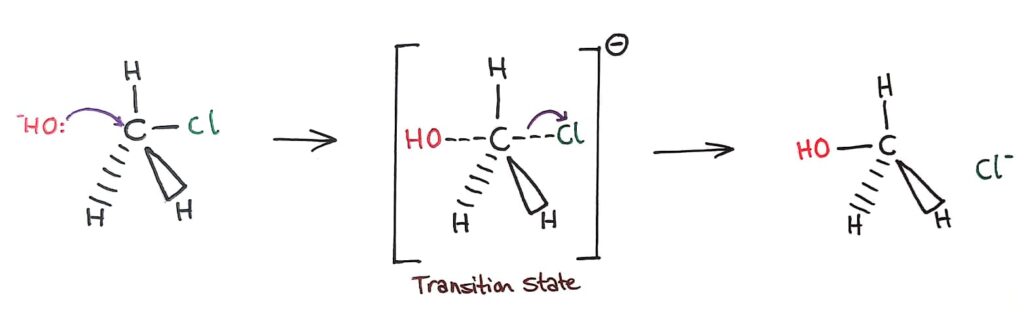

In SN2 reactions, the nucleophile forms a ‘5th bond’ with the central carbon to form an unstable transition state. The C-Halogen bond then breaks and the new product is formed.

SN1 vs SN2

For tertiary halogenoalkanes the predominant mechanism is SN1 and for primary halogenoalkanes it is SN2. Both mechanisms occur for secondary halogenoalkanes.

The rate determining step (slow step) in an SN1 reaction depends only on the concentration of the halogenoalkane, rate = k[halogenoalkane]. For SN2, rate = k[halogenoalkane][nucleophile]. SN2 is stereospecific with an inversion of configuration at the carbon.

SN2 reactions are best conducted using aprotic, non-polar solvents and SN1 reactions are best conducted using protic, polar solvents.

Explanation of how the rate depends on the identity of the halogen (ie the leaving group), whether the halogenoalkane is primary, secondary or tertiary and the choice of solvent.

Outline of the difference between protic and aprotic solvents.

SN1 and SN2 have a lot of similarities and differences in their mechanisms. Below is a table summary and a quizlet test to help you remember them 😃.

SN1

SN2

Rate of Reaction

- Rate determining step is breaking carbon halogen bond

- Rate=k[Halogenoalkane]

- Faster than SN2

- Depends on both reactants

- Rate=k[Halogenoalkane][Nucleophile]

- Slower than SN1

Solvent

- Polar protic solvent

- Stabilises the carbocation intermediate

- Forms hydrogen bonds

- Polar aprotic solvent

- Does not form hydrogen bonds

Mechanism

- Forms an intermediate

- Stable (to an extent)

- Forms a transition state

- Unstable

Primary or Tertiary?

- Tertiary halogenoalkanes

- Steric hindrance (bulkiness) physically stops tertiary halogenoalkanes from undergoing SN2 reactions

- Primary halogenoalkanes

- Primary carbocations are too unstable

Electrophilic Addition

Deduction of the mechanism of the electrophilic addition reactions of alkenes with halogens/interhalogens and hydrogen halides.

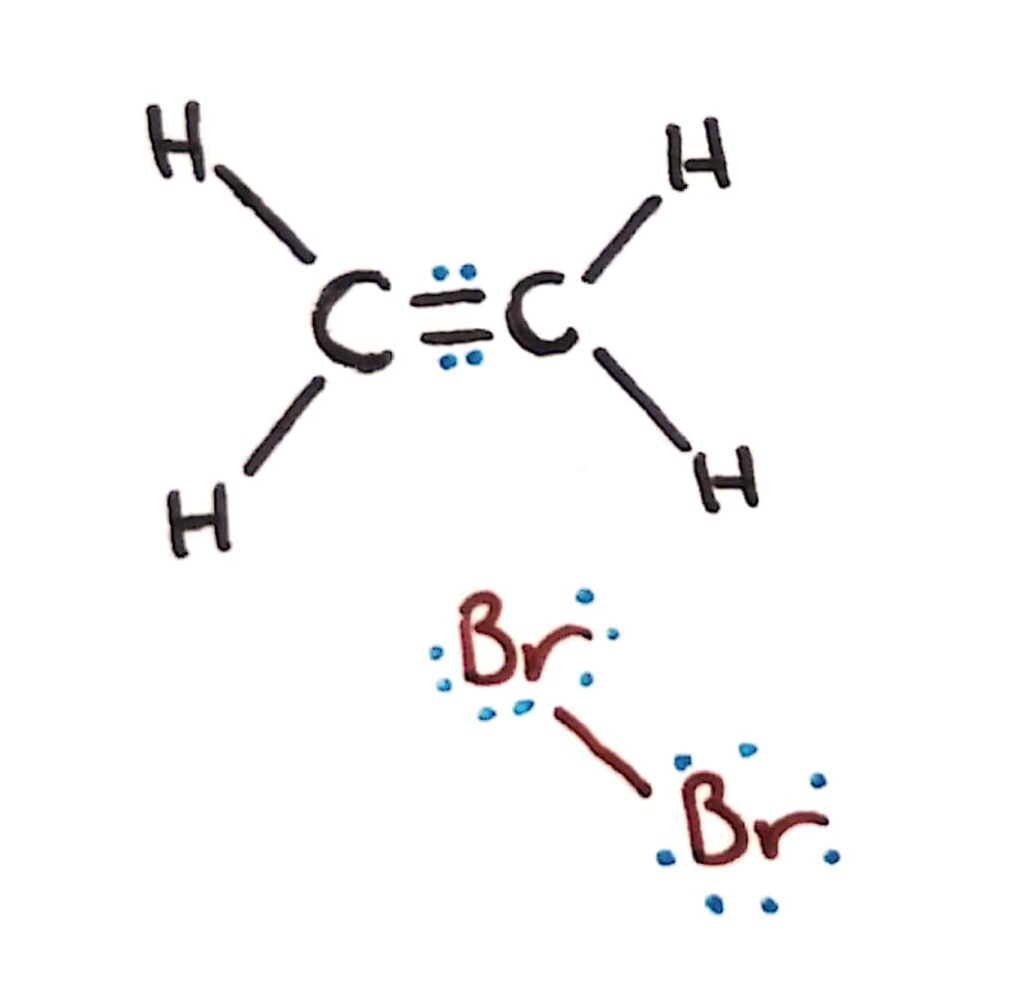

Electrophilic addition is essentially addition across a double bond. It’s electrophilic because an electrophile reacts across the electron rich double bond.

Bromine alkene addition reaction

When a bromine molecule approaches an alkene, the electron rich double bond acts to repel the electrons in the bromine molecule, forming a temporary dipole. This is an example of an induced dipole!

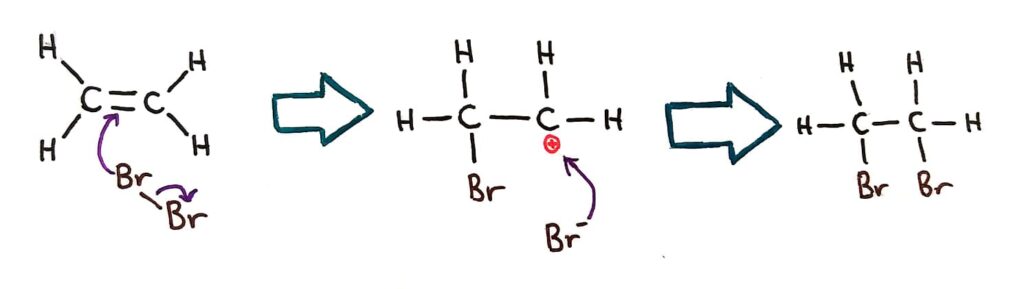

This induced dipole causes a bromine atom to become positively charged and bond across the double bond, splitting open the double bond and creating a positive carbocation. The other bromine (Br- now) then bonds at the positive carbon.

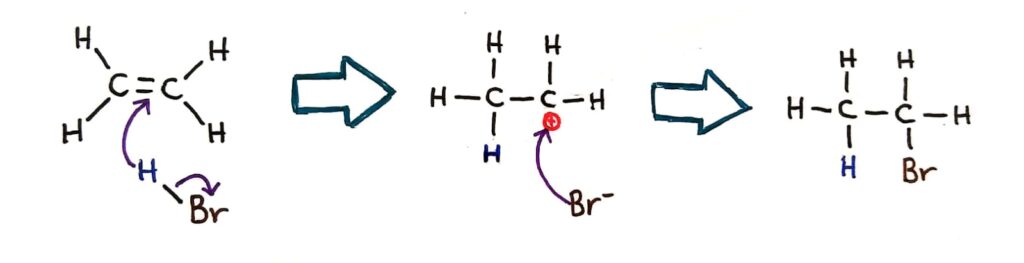

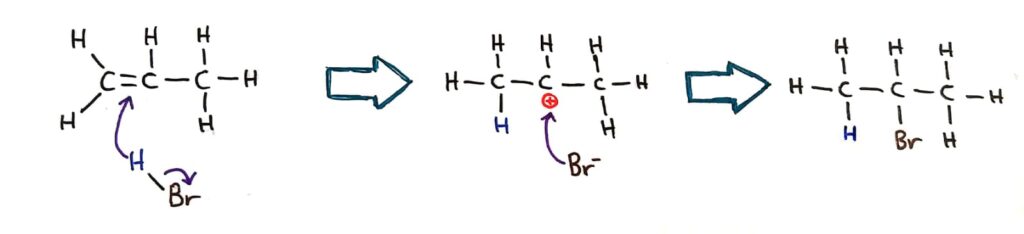

Hydrogen bromide addition reaction

Hydrogen halides (e.g. HCl, HBr) react in pretty much the same way.

Markovnikov's rule

Markovnikov’s rule can be applied to predict the major product in electrophilic addition reactions of unsymmetrical alkenes with hydrogen halides and interhalogens. The formation of the major product can be explained in terms of the relative stability of possible carbocations in the reaction mechanism.

Markovnikov’s rule tells us where the positive charge will form in the case of larger alkenes.

Markovnikov’s rule says that the hydrogen will always bond to the carbon that is already bonded to the largest number of hydrogens.

The reason for this is due to the positive inductive effect, where the positive charge is stabilised and ‘spread out’ by the adjacent carbons.

Electrophilic Substitution

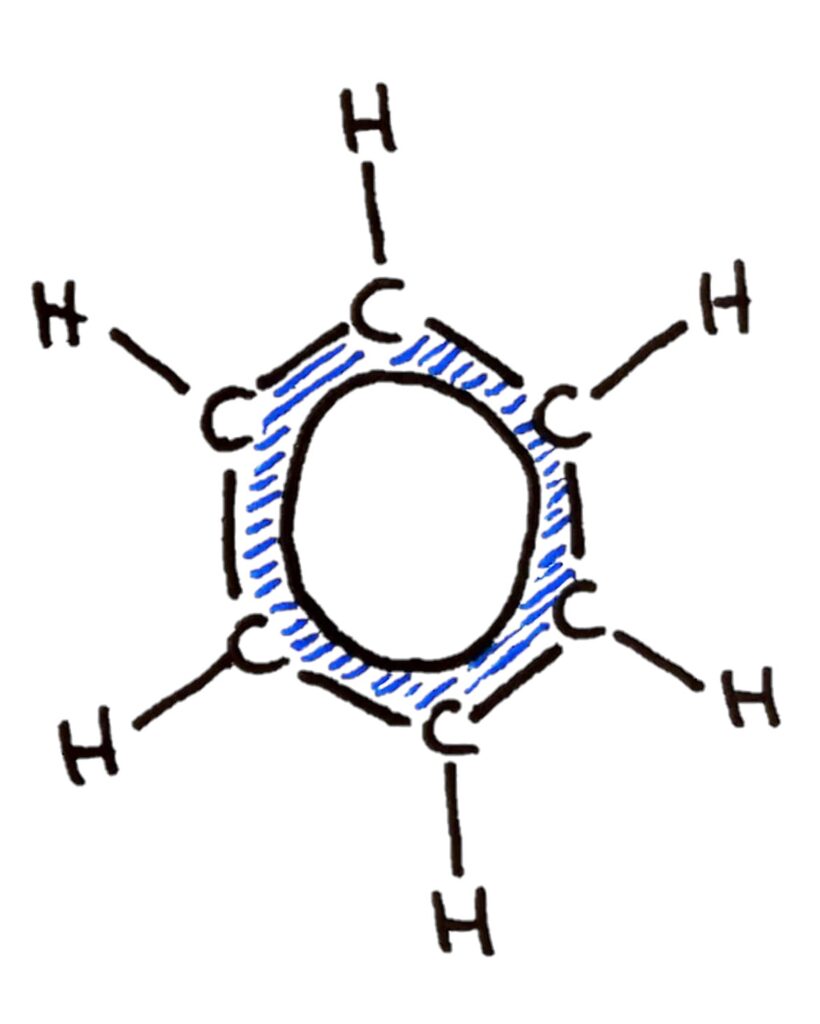

Benzene is the simplest aromatic hydrocarbon compound (or arene) and has a delocalized structure of p bonds around its ring. Each carbon to carbon bond has a bond order of 1.5. Benzene is susceptible to attack by electrophiles.

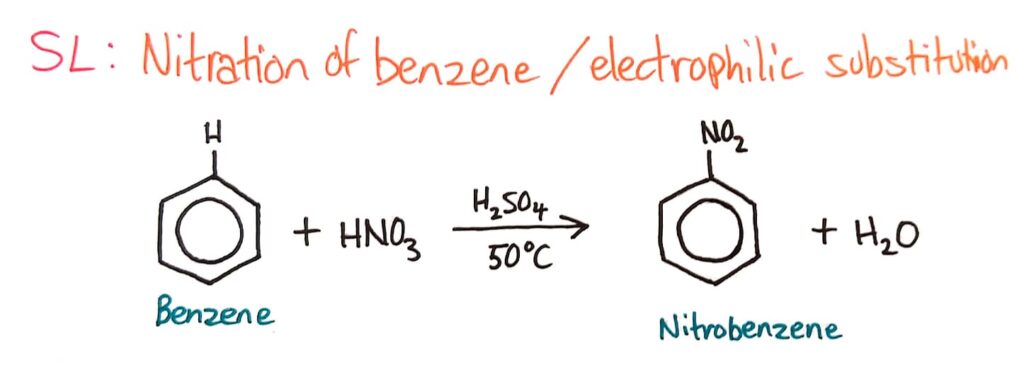

Deduction of the mechanism of the nitration (electrophilic substitution) reaction of benzene (using a mixture of concentrated nitric acid and sulfuric acid).

Benzene, because of it’s delocalised pi electrons is also susceptible to attack by electrophiles. The benzene ring is a very electron rich area.

Benzene however doesn’t really have double bonds because of resonance (terms and conditions may apply) so it doesn’t undergo addition reactions. Benzene undergoes electrophilic substitution reactions instead.

Topic 10 teaches you the basics of electrophilic substitution; the basics, but in topic 20 we go into the mechanism of the reaction.

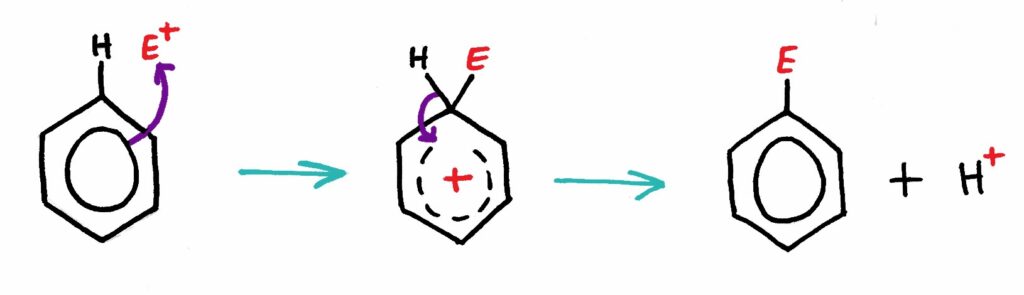

The Mechanism

Benzene’s electron dense ring is attracted to the electrophile. The electrophile then bonds with the benzene ring, temporarily disrupting the resonance structure. The C-H bond then breaks and the product is formed.

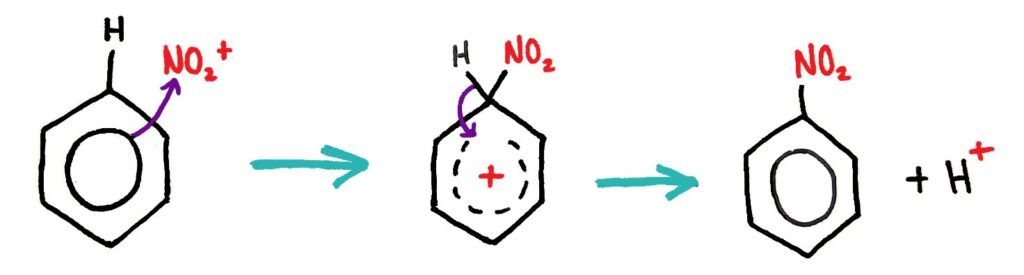

Nitration of Benzene

The same mechanism occurs in the nitration of benzene reaction, where NO2+ reacts with benzene to form nitrobenzene.

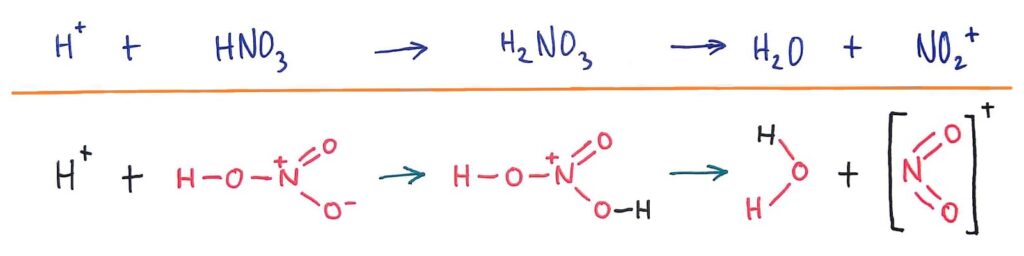

Generation of NO2+ electrophile

The NO2+ electrophile is generated from the H2SO4 catalyst and HNO3. H2SO4 donates a proton to HNO3 to form H2NO3 which then breaks into NO2+ and H2O.

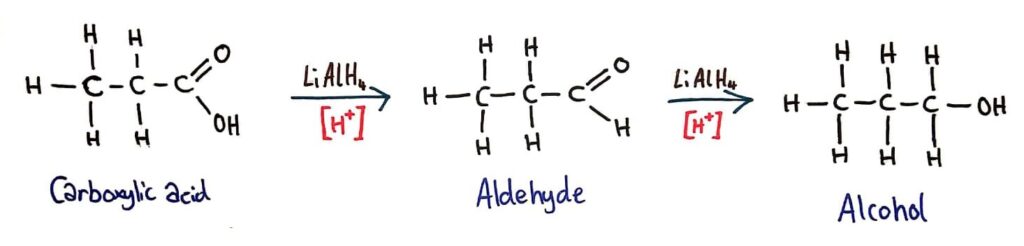

Reduction

Carboxylic acids can be reduced to primary alcohols (via the aldehyde). Ketones can be reduced to secondary alcohols. Typical reducing agents are lithium aluminium hydride (used to reduce carboxylic acids) and sodium borohydride.

Writing reduction reactions of carbonyl containing compounds: aldehydes and and ketones to primary and secondary alcohols and carboxylic acids to aldehydes, using suitable reducing agents.

The mechanisms for reduction are effectively the reverse of the the oxidation reactions studied in topic 10.

Carboxylic acids can be reduced to aldehydes and primary alcohols by LiAlH4 (reducing agent) in acidic conditions.

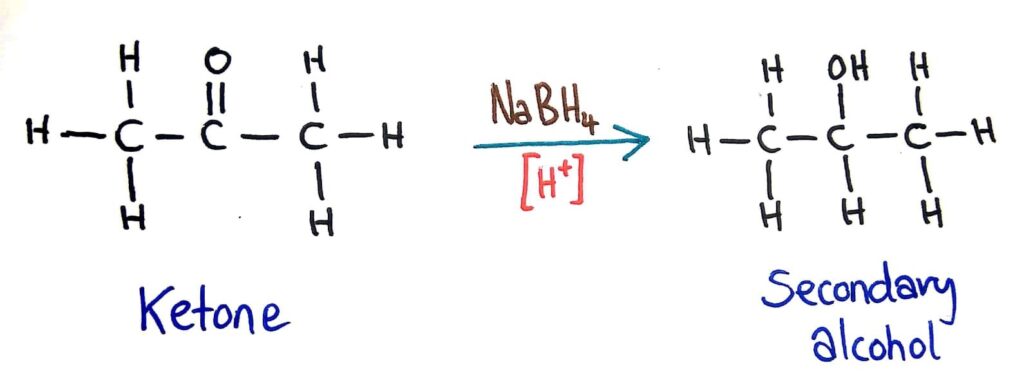

Likewise, ketones can be reduced to secondary alcohols by a reducing agent (LiAlH4 of NaBH4) in acidic conditions.

Reducing agents

The two most commonly used reducing agents are NaBH4 and LiAlH4. It’s better just to say LiAlH4 though because it can be used for all reactions whereas NaBH4 can only be used for some.

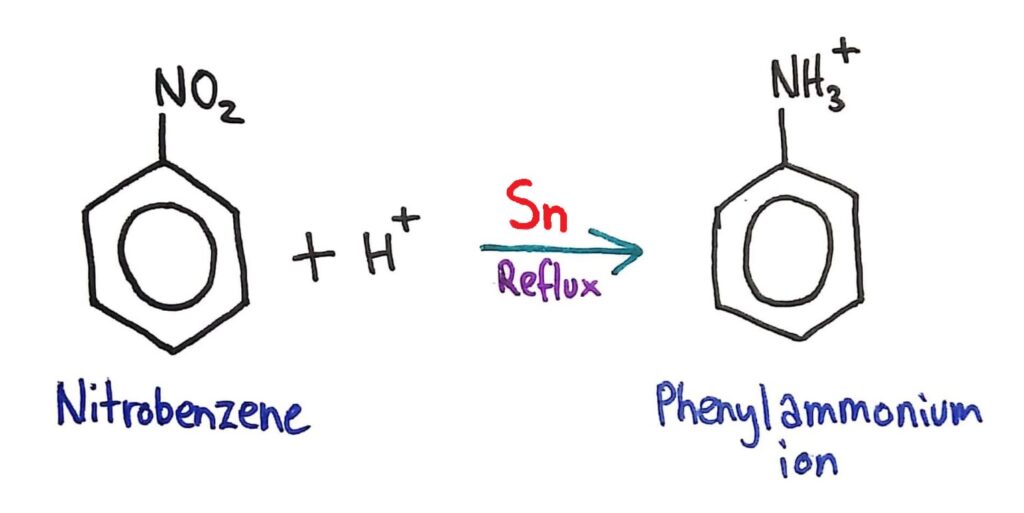

Conversion of Nitrobenzene to Phenylamine

Conversion of nitrobenzene to phenylamine via a two- stage reaction.

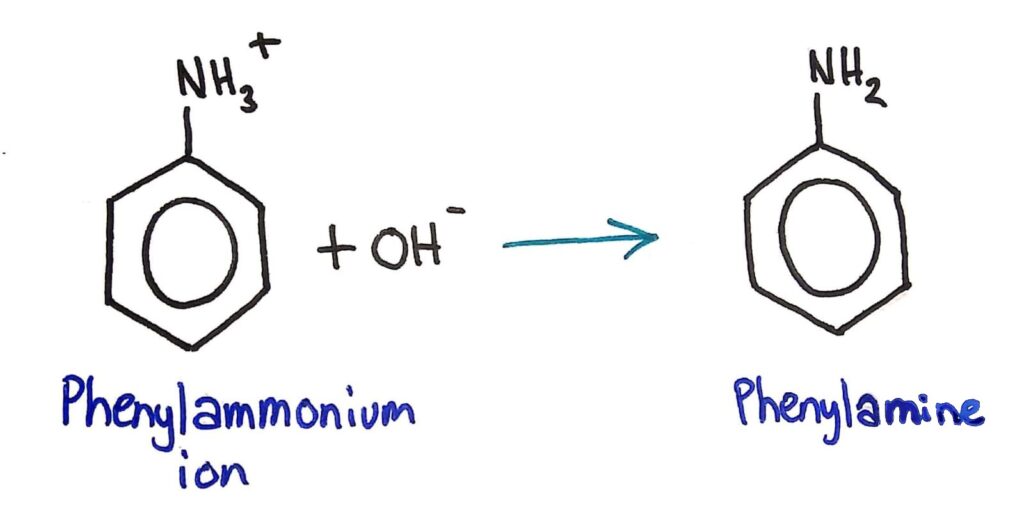

This conversion of the NO2 group to an NH2 group is done in two steps.

1. Nitrobenzene is converted to the phenylammonium ion by refluxing it with concentrated HCl and a tin (Sn) catalyst.

2. OH- ions (usually in the form of concentrated NaOH) are added to convert the phenylammonium ion to phenylamine.